The baseline

This article was born as a consequence of this reading. I like the idea of shifting baseline a lot, it’s a tool to fight our committment with the current epoch, a strategy to look behind us and take the time to measure changes. Since I’m quite interested in the topic of online privacy, I made this article very focused on that too. I think that although not always easy to measure, the effect of privacy loss is going to severely shape the future of our democracies and humanity as a whole.

Few weeks ago I run into a blog authored by a guy that happened to live in Antarctica few months. Among the different stuff he writes about, there’s an interesting article focused on his experience using everyday apps and software in such extreme conditions. That scenario is a real corner case, but got me thinking about all the stuff that I daily use and how I set my benchmarks for what I consider normal. What’s a normal personal data request by a website? What’s a normal internet bandwidth? How many seconds am I willing to wait for the webpage to load before thinking uhm, there’s something going on here!

My answers to these questions are different than yours, probably. Just like people living in remote locations have a different perception on what’s essential or not for their daily life.

For example we1 are used to download tons of ads and trackers whenever web surfing: that expectation is our baseline for the online experience anytime we are browsing the internet. If a website takes more than, say, 2 or 3 seconds, we consider it slow. And possibly we point to the hardware as the problem: ‘look, my laptop is very slow lately, I’d be better off buying an another one’.

Ultimately, we are so used to our moving proxies that we miss the big picture, we don’t consider that if comparing our internet experience with the web surfing experience 15 years ago, today’s baseline is very very high.

Shifting Baseline

In 1995, an article titled Anecdotes and the shifting baseline syndrome of fisheries was published on the Trends in Ecology and Evolution journal, and that article is the genesis of the expression shifting baseline.

Daniel Pauly studied the overfishing phenomenon and undestood that the perception of the fishing catastrophe was lower than it shoud have been, probably because of a bias of the biologists that were researching the pheonomenon. Specifically, Pauly understood that generations of biologists were missing the big picture in these trends, they were not considering earlier knowledge and old benchmarks in their analysis. The result of it was that despite being attentioned and possibly some precautious taken, the compounded results of overfishing for the oceans equlibrium was way worse than what was suggested by the isolated misurations thoughout the decades.

That article, being a 30 years old article about fishing - topic on which I know nothing about - opened my mind to a moltitude of other examples of situations where our perception of a phenomenon and its impact is severely polluted by our choice of poor, questionable or expired benchmarks.

The freezing price of ice-cream

Most of the time we consider what we always saw and what has always occured as the base scenario, the baseline for our interpretation of the world. For example, when I was a child I used to go out with my parents and take an ice-cream once every few weeks. For one ice-cream flavour we usually payed €0.802.

As years went by, prices increased and an ice-cream next to my place, at the same exact ice-cream maker shop, now costs roughly €1.70 a flavour, variation that occurred in almost 15 years. I don’t want to make this article about ice-cream prices, but that’s a clear example of how a person perceives a baseline: my cheapest ice-cream was €0.80, my father’s cheapest ice-cream was 100 lire (roughly €0.05). I’m benchmarking some phenomenon (ice-cream price) based on my personal experience and not including historical prior knowledge. If I where to find an ice-cream maker shop selling ice-creams for €1.00 a flavour, I would be considerably happy. My father may be too, but still he would be paying 20 times the price he was used to as a child.

Over the course of decades, our perception tends to dilute the benchmarks that people before us had: a drop of 10% of fish in an ocean for every decade makes the 100 years change of almost 70% from the initial baseline, but if we focus only on the

the amount of fish in the ocean is decreased of 10% the last decade

we tend to miss the big picture. Which is that we’re basically running out of fish.

Privacy

The shifting baseline principle is one of those ideas that once you learn it once, it never leaves your mind. It’s a tool that can help you to catch nuances in complex topics, where usually we suffer the influence of media, time and poorly set proxies3.

With the noisy scandal of Cambridge Analytica and, before that, the findings brought to light by Edward Snowden, we all thought that people finally had the tools, time and interest into changing their behaviour towards social media. That scandal brought to light the possible crippling effects of tech giants abuses, the importance of having some sort of individual filters, awareness of what we see and do on the internet.

What have we learned from that?

Not much, apparently.

Yes, some institutional efforts were made, GDPR was born, an unknown number of committees were created. But ultimately the power is in the people that use social media, and people are still massively using social media4.

Data lakes without fences

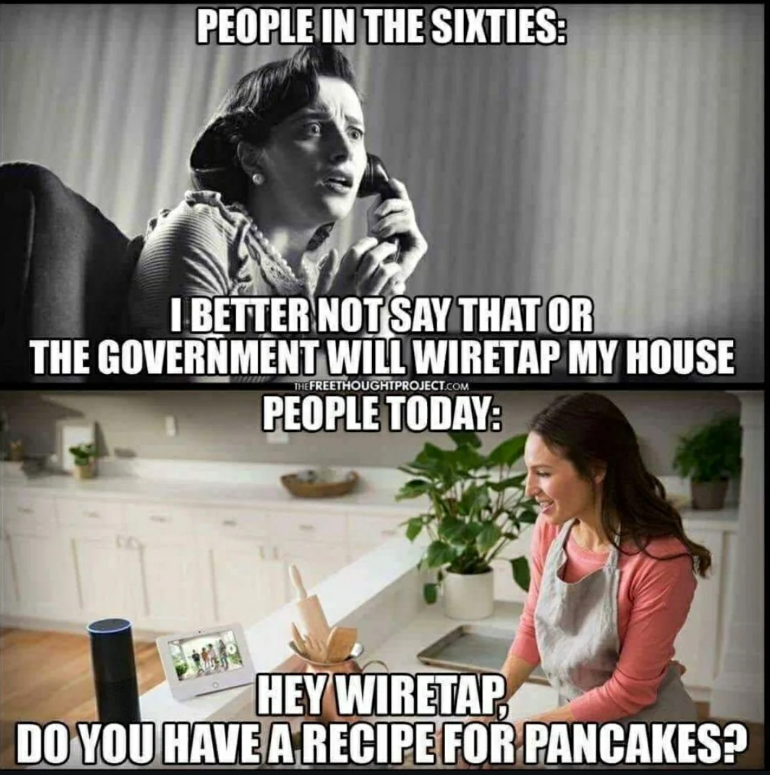

Throughout the decades, the citizens of the internet got used to an increasingly high number of abuses from big techs. The collection of user data for some fair use quickly become an opportunity for harvesting user data for future uses. We got used to put our telephone number in every website “just to get notifications”, even when that is effectively not needed for the service; companies started to ask more and more information about us. Government and institutions started to collect a ton of data too. All in the name of democracy, off course.

After all, who doesn’t trust their government?5

The hidden truth of data collection is that it’s easy to collect data, the difficult thing is to protect it properly, having the correct infrastructure and personnel. If that is not the case, it’s a matter of time for some criminal to attack you.

Technology is not bad

Nowadays, our baseline for creating a new brand email address is to be asked the telephone number, to not create the account using a VPN or Tor, to let the provider access to all our email materials. We are used to let Google access all our Google Drive content. They say it’s to prevent fraudulent use, but at the end they kill two birds with one stone and use the data for commercial purposes, like training their AI models.

We are used to have the Google Play Services on our phone running 24/7, just for the sake of receiving notifications instantly. Nice, we receive notifications, Google reads them all too. And we are fine with that, like if our grandparents were to get every mail in their mailbox read by the postman just to be quicker in the delivery.

We are used to post our private stuff in the open, to send nudes through totally not encrypted social media chats. We send chat messages every day using platforms that are monitored by tech giants, crawling all the metadata and building our social graphs to understand how to better engage us with their products. Telegram, that is widely used in Europe, is run by a no profit institution that somehow raised more than $700 mln since its inception and has a provably broken end-to-end encryption schema at the core of its product. But we still send us important messages through this platform, that is born in Russia and possibly still has some links with the Kremlin.

We are used to the redundant KYC procedures of banks, even though it’s been 15 years since someone invented a technology to send each other value online without having to put our IDs everywhere.

Smartphones cameras track our eyes position, measure if we are engaged, use this data to sell us more ads.

All this technology is also used for good: computer vision stuff can help disabled people, can improve the deaths-on-the-road statistics. Digital communications can temporarly make us close to the farthest person on the planet. Technology is not innatively bad or good, it’s a tool.

What we’re used to do today is the baseline for future generations, but it has become our own baseline too. My parents didn’t have a way to communicate real time between each other, but also didn’t give all their purchase information to an oligarchy of credit card companies that nowadays control our economic life day-by-day.

Get up and walk

We’re never too late for changing what’s going on. What’s needed is the willingness to put into the work, to get our hands dirty with technology at the expense of some sacrifices, some loss of comfort.

The baseline for privacy today is very low: it’s leaving every private financial data in the hands of commercial companies just to protect the kids. It’s giving anyone with some OSINT knowledge (or admin access to some databases) to see exactly who we are, where we leave, how much we earn.

I vividly remember the day my father came back home with the first smartphone. I was in high school and I knew that for him that was a complete revolution. Something that used to have buttons, now is a thin, shiny smartphone. His baseline for telephones was the cabin on the street when he was a young boy, my baseline became that smartphone. Throughout the years I got used to change, but I have some vague memories of how was to use that smartphone of 14 years ago and that is how I compare my current experience with the baseline.

I remember when I created my social media account on Instagram, when I created my first email address. There were basically no ads on youtube nor on any social media, in fact I was very annoyed when the first ads started to appear on the instagram feed. Now is not like that anymore and I don’t want to blame anyone for it, it’s just how things flow through time.

But still, users used to have way more privacy online, they also used to seek it. Now if I look at our habits with regards to privacy, I feel that we’re in a similar situation to the overfishing scenario that Daniel Pauly portraied: we sit on the belief that we’re losing a bit of privacy (for good reasons, we believe) and we still have the other 90% to fish. But in reality, that 10% is not considering the compounded effect over decades.

This is how the baseline shifted.

Dragging back the fence

At the end of the day, even though it’s a macroscopic phenomenon, baseline shifting is all about individual experience and perception. It’s rooted in how much self awareness we put into every action, in how often we tend to look back at the past to gain some lessons about ourselves.

I don’t see looking at the past to measure changes as luddism, I see it as a way to grasp more knowledge about society and ourselves. Measuring how our baseline shifted is how we can undestand if we’re on the wrong relationship, because maybe we started to accept things we hate. It can help us to understand if we’re doing the job we don’t like, but also can help us understand if we are improving our skills and thus we need to aim higher.

A given baseline can move in both directions, there’s always room for improvements, which sometimes mean putting the baseline a bit ahead, and sometimes mean inverting a trend. Society can understand the importance of preventing overfishing just like individuals can understand the importance of preventing privacy losses.

And possibly do something about it.

Civilization is the progress toward a society of privacy. The savage’s whole existence is public, ruled by the laws of his tribe. Civilization is the process of setting man free from men. (For the new Intellectual - Ayn Rand)

-

No, I’m lying here: I’m not used to online ads. If you are, then it means you need to take a quick look at what an ad blocker is. Thank me later. ↩

-

I know that prices are not decided on the how I would like it to be basis, moreover economics thought me that sometimes supply and demand equilibrium can be a (widely) moving target. Still, those ice-creams were the cheapest of my life and that €0.80-a-flavour price is still the lowest price I’ve ever run into. ↩

-

I already gave a quick example about the effect that shifting baseline has on our perception of money and purchasing power: that’s a slippery slope I’m not going to fall into today, it will be for another article. ↩

-

Don’t get me wrong, I don’t think social media is innately wrong, me myself use them to have a window on the world, particularly for networking. That’s probably a fair use. ↩

-

According to Planetica, almost 50% of the victims of cyber attacks in Italy in 2021 was somehow associated with the public sector, being it education, healthcare, Telecomunications, transportation or government bodies. For example, the ransomware gang Ransomcortex is specialized into attacking healthcare structures, that usually collect huge, redundant amounts of data, without much sophisticated infrastructure to deal with it safely and with personnel not adequately trained to protect digital information. ↩